Sam Linguist

STOWAWAY is pleased to present Sam Linguist, a solo show by Brooklyn based Sam Linguist. The artist presents 7 stoneware works installed from the cieling and walls of the gallery. Please join us for the opening reception Saturday, May 17th, 2025 from 5-8 pm.

Super-Matte Strata

by Natalie Power

There’s a certain ugliness afoot in the days after Christmas. Everybody’s depletion is made bald; the veil of happy artifice goes up. The days before New Year’s stall all regular space-time programming. Hours stretch inexplicably on––not day, and not night, either.

Some people savor these last days of culturally-enforced joy. They revel in the final notes of Bing Crosby’s croon; they gratefully continue watching The Grinch. But I cannot be rid of the season quick enough. The tumbleweeds of wrapping paper are an affront to my eyes. All of the lights––twinkling, sweet, mere nights ago––are garish clutter in the face of unflinching January. Christmas Eve’s cheeses are calcifying in the fridge, stacked behind a quart of eggnog that will go unfinished. All is evidence of misguided excess, of the sun going down on youth. And I want it raked away. I want spring, and then summer, and then Halloween all over.

When I announce this sentiment––that the post-Christmas comedown is relatively unbearable––Sam and I are driving to my niece’s eighth birthday party.

I kinda love this time, Sam says back to me. Everything’s all deflated. It’s sort of awesome.

We are going past an inflatable Abominable Snowman in somebody’s yard as he says this. The yeti’s arm is, technically, not all deflated; it’s raised, swollen in a show of greeting. But this is Sam’s way: bizarro optimism. It is his dogged admiration of unsung, utilitarian structures and phenomena. He is drawn to liminalities that some would purposefully avoid; this is how he consumes so much looping, postmodern saxophone music.

I do not press the issue because we arrive at the birthday party, which is happening at the indoor trampoline park––a somewhat recent convention for our hometown, boasting roomfuls of trampolines and foam pits upon which children can throw their bodies. It is tucked into a shopping strip that once housed our most precious establishments: the movie theater, the pizza place, the Chinese place, the Tex-Mex place and the doctors’ office.

But these bastions of commerce have long-since departed. They have scattered and, like moths, been drawn toward light: a new, all-cement shopping center erected in the early aughts. If they haven’t relocated, they’ve died out completely, unable to keep pace with the Chick-fil-A and the Target and the Claire’s across town. The only establishments with enough grit to withstand the shopping strip’s mass exodus are places of pure lawlessness: Applebee’s and Big Lots. And it is directly behind this Applebee’s––and to the right of Big Lots––that my niece’s birthday party is unfolding.

Inside the trampoline park, she and her friends are roving around in a gaggle, their faces splotched with exertion, their hairlines dewed. They clamber over to a monorail-like contraption where children are lined up for a turn. It is a miniature zipline that they wait for, situated just above a comedically unsafe mouth of concrete.

An employee pushes harnessed kids from a platform, and once in motion, they look like sacks of clothing in a dry cleaners’ shop. They look like giant, cumbersome hooks moving about a shower curtain. And I wince whenever they make a turn, their skeletons jerking over the pit of bone-breaking material. But they are unbridled in their airborne joy. They are unfazed by the unsightly deathtrap over which they are flung.

Did that used to be a swimming pool? I say to Sam, pointing to the canyon beneath them. I thought this used to be Cici’s.

This was Muscle Works, Sam says: the long-defunct exercise place, which did, in fact, include a chlorine pool. Cici’s was further down.

Muscle Works, I think. Where my childhood best friend’s mom worked until its closure; she was an aerobics teacher. I picture her––severe woman who’d long since moved to Louisiana––in sportswear, popstar microphone hung along her jaw, pacing the lip of this now-empty pool while barking encouragement at her clients. I think next of Cici’s Pizza, which also once existed a couple doors down, replete with its arcade and gargantuan television––a gorgeous monstrosity that screened perpetual Cartoon Network as patrons shoveled buffet pizza into their mouths.

Now we are standing inside of the unrecognizable husk of these haunts. We are in the freshest iteration of the building, its youngest epidermis. Muscle Works is history; Cici’s has rebranded and nestled beside Target.

Everything on this end of town used to be something else; shops eke into one another’s shells like naked hermit crabs. Where Pet-O-Rama once stood is now an Italian restaurant; a faith-based ammunition store operates in what was formerly Hallmark. The old movie theater houses an entire nondenominational church. Burger King ceded its ground and replanted right inside Walmart, just beside an in-store salon that smells of singed hair and hot foil; in Burger King’s wake is now a sushi drive-thru.

And perhaps this––perpetual reincarnation––is the best case scenario. Because the alternative here, it seems, is to cobble a place down entirely. Or else slather it in a coat of white paint: a move made popular by the home renovation people with the TV show down in Waco. They’ve made a killing peddling price-gauged votive candles and evangelizing on shabby chic mystique; they have convinced a large portion of the population that a clean slate––painted white, or eggshell, or cream––is the pinnacle of taste.

And maybe the old shopping strip––with its dark brick and crumbling parking lot and tinted storefronts––is a direct affront to such misguided minimalism. Perhaps it’s even punk: dissent from the suburban sheen. Perhaps this shopping strip is the future. Perhaps it’s the final frontier.

There is a reason A24 leans so heavily upon grainy saturations of the nineties and aughts. And there is a reason hyperpop––half-video game, half toddlerhood dream––so easily worms its way into our ears. There is a reason that half of the internet is dedicated to remembering days of yore: accounts devoted to widespread nostalgia, obsessions with anemic and dying malls. There is a reason that Rainforest Cafe and Chili’s are experiencing real-time resurrection. Spaces of the past are, theoretically, beguiling. And irony, when deftly employed, can signify revolutionary taste; take the Dimes Squarekids, decked out in blue collar garb and discarded Southern thrift.

But to actually inhabit a liminal space––to enter the belly of the beast and pass multiple, actual hours in the windowless trampoline park in what used to be Muscle Works behind the Applebee’s––is not for the weak. And to even ascribe some kind of poetry to it, I realize, might actually be bullshit: a metropolitan knee-jerk. The truth of the matter is that the trampoline park is gaudy, and loud, and devoid of any aesthetic harmony. And to those of us with more sensitive constitutions––individuals who cannot withstand even a post-Christmastime hangover––it can be a challenge to find any redeemable quality in a place so inundated with neon pleather.

But Sam, I have learned, will extract worth from even the most derelict reaches of suburbia.

That is amazing, he declares, pointing upward.

The thing he motions to is a three-headed TV, screening multiple iterations of children’s entertainment: Bluey on one, Spongebob and a Disney sitcom on the others. The screens are affixed to a steel structure that reaches down, blank and austere, like a claw machine’s opened maw. How any children could possibly absorb this overhead entertainment amidst such plentiful, eye-level stimulation is beyond me. And yet they ogle at the screens above, open-mouthed, as the birthday cake is cut and dispersed.

I know immediately that this is source material for Sam. I can tell by the awe in his tone––not unlike the reverie he expressed over post-Christmas deflation. And it is little wonder to me; I have witnessed this transmission a hundred times over. It is an primal impulse of Sam’s, a Lynchian inclination to plumb the depths of what is so seemingly, uncannily regular. It is pointedly not nostalgia, and not irony, either; it is the pursuit of some transitory space between absurdity and gravity. And perhaps this veil is thinnest in a locale such as ours: a small town bursting from its buttons, sprawling at warp speed, pantomiming big-city swagger while leveling its own trees in the name of expansion.

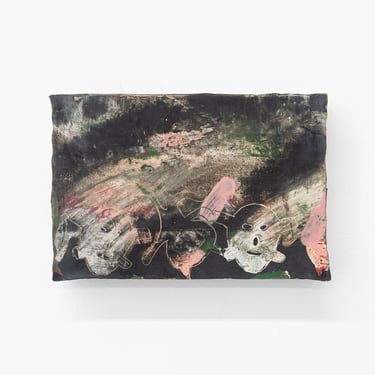

The substance of the paintings only emphasizes this simmering chaos, the infinite pixels of amusement and violence and oddity and ache that make up our psychological snow. The works depart from any tidy plane of subject matter, flickering instead between imagery and abstraction, oscillating between pulp and the macabre. Their surfaces mimic channel-surfing; viewers are subjected, in any one sitting, to frames of canned laughter and scripted discord and campy slashers and flaming cars and puppets incanting the ABCs. To experience the work is to ingest it as programming––blend of bytes and hues ground up and cast through airwaves, then flattened into scenes that are at once forebodingly familiar––even pleasing––while simultaneously, morbidly surreal.

Even Sam’s modality––and medium––is reminiscent of the trampoline park inside of the perpetually repurposed shopping strip. He enacts his own forms of reincarnation, making an entire painting and then another atop its surface the following day. He carves inscriptions into underglaze and covers his own tracks; he hand-pixellates his works and smudges formations of color with tap water. Layer upon layer upon layer is deployed upon his ceramic canvases; what ensues is a super-matte strata––loaded and yet deceptively smooth for all of its painstaking gradation.

What Sam has invoked is material samsara. And he comes by it honestly––a proclivity for retail space-based comedy, a keen sensitivity to seemingly mundane––or else plainly uncomely––conventions. Though his approach is hardly comparable to that of the realtors’ and the developers’ and the home renovation people with the TV show down in Waco; Sam is not looking for some diamond in the rough, is not hellbent on manufacturing any sexiness or polished novelty. Instead, he relishes the gaps borne of this rabid and misguided push for modernity.

And while he does experience bouts of his own suburban delirium––most pointedly, an aversion to all-beige subdivisions––he does not seek to make any mockery of the peculiar ecosystem from which we hail. Rather, his works are something of a nonconscious homage to its ephemera, ever at risk of being mowed down or painted over: shuttered structures encasing near-wordless, earliest-remembered sensations and a die-hard insistence on their continuum.